Math and Art

Mathematics

is the language that governs nature. Everything from proportions and patterns,

to colors and sound is expressed with math just as humans are defined by DNA. I

remember really grasping this concept for the first time and becoming

fascinated in elementary school when viewing the Disney short film from the

1950s, Donald Duck in Mathmagic Land.

The golden rectangle, the concept of pi, and perspective are numerical patterns

that govern the visual world.

"All nature's works have a mathematical logic, and her patterns are limitless."

Throughout history, many artists

have employed math as a tool to make their art as realistic and/or appealing as

possible. One example is perspective. It is a critical geometric technique that

allows for two-dimensional drawings and paintings to appear three-dimensional

and life-like. Perhaps most notably, Leonardo DaVinci’s work intricately weaves

the golden ratio into many of pieces to evoke what he viewed as “ideal human

proportions”. Fractals, intricate patterns that are of the same repeated shapes, are yet another example of mathematics being employed to create life-like art.

Throughout history, many artists

have employed math as a tool to make their art as realistic and/or appealing as

possible. One example is perspective. It is a critical geometric technique that

allows for two-dimensional drawings and paintings to appear three-dimensional

and life-like. Perhaps most notably, Leonardo DaVinci’s work intricately weaves

the golden ratio into many of pieces to evoke what he viewed as “ideal human

proportions”. Fractals, intricate patterns that are of the same repeated shapes, are yet another example of mathematics being employed to create life-like art. Although many artists use mathematics

to create realistic work, it is almost as appealing for artists to use mathematics

to defy what we would perceive as normal. In Flatland, a world is envisioned governed by the same math as ours,

but with one less dimension, and the result, although unrelatable, is

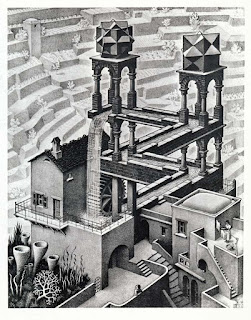

fascinating. Another example of an artist using math to bend reality in art is M.

C. Escher. By adhering to almost all the mathematical and geometric principles

of the real world, and deliberately defying a few, Escher creates perplexing

images that appear real at first glance but jar the brain the more a viewer

looks. Waterfall, takes a closed loop

system and twists it into two impossible triangles to transform a common and

logical scene form the real world into a optically confusng scene.

Although many artists use mathematics

to create realistic work, it is almost as appealing for artists to use mathematics

to defy what we would perceive as normal. In Flatland, a world is envisioned governed by the same math as ours,

but with one less dimension, and the result, although unrelatable, is

fascinating. Another example of an artist using math to bend reality in art is M.

C. Escher. By adhering to almost all the mathematical and geometric principles

of the real world, and deliberately defying a few, Escher creates perplexing

images that appear real at first glance but jar the brain the more a viewer

looks. Waterfall, takes a closed loop

system and twists it into two impossible triangles to transform a common and

logical scene form the real world into a optically confusng scene.

Along with colors, and shapes, and

shading, math is another avenue with which artists can define their work. It is

a valuable tool that can be abided to strictly to develop the most true-to-life

art from a physical perspective, or can be manipulated, like in the case of

Escher, to deliberately distort physical appearance.

Vesna, Victoria.

“Mathematics-pt1-ZeroPerspectiveGoldenMean.mov.” Cole UC online. Youtube, 9

April 2012.

Smith, B. Sidney. "The

Mathematical Art of M.C. Escher." Platonic Realms Minitexts. Platonic

Realms, 13 Mar 2014. Web. 13 Mar 2014. http://platonicrealms.com/

Luske, Hamilton, director. Donald

Duck in Mathmagic Land. Walt Disney Pictures, 1959.

Jonathon, Wolfe. “What Are

Fractals?” Fractal Foundation, 2015, fractalfoundation.org/resources/what-are-fractals/.

Abbott, Edwin A, and Lila M.

Harper. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Peterborough, Ont: Broadview

Editions, 2010. Print.

Oullette, Jennifer. "Pollock’s

Fractals." Discover. November 1 2001. Discovermagazine.com.

Hey Stephen! As I first open your blog I thought it was pretty funny that you had Donald the Duck on your post but as I continued to read your blog, I really like how you tied it into what we are learning. I also enjoyed reading about your examples on perspective and dimensions. We often overlook how intertwined the two disciplines are and I feel that the use of geometry in dimensional drawing is a great example that demonstrates this. As you mention, Da Vinci used geometry a lot and so did numerous other artists such as Picasso. Lastly, I really enjoyed how you listed and talked about various examples such as Waterfall and Flatland and your take on the work!

ReplyDelete